When people present this argument against the EU I’ve tended to respond by looking at ways to help in the regeneration of Greece. This is not to say a tough approach is always best, and there have been raw feelings among the Greeks going back to the second world war, but I’ve tended to argue that the route the EU took is probably the fastest to re-stabilise Greece.

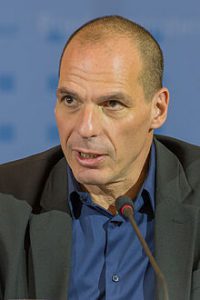

In an interview with Owen Jones in The Guardian Varoufakis begins by pointing out that Brexit would leave the UK much more exposed to TTIP. At the moment (April 2016) it is not clear what the final text of TTIP will be, but Varoufakis is clearly right that, within the EU, we have the capacity to influence things, where outside we could do little more than accept what we are offered. He continues:

“The left should never lose sight of the 1930s. After 1929 the left failed to create the coalition with other democrats that was necessary to prevent the descent into the abyss of the 1930s.

“I see such an abyss opening up in front of our eyes in the centre of Europe. If it does, we are going to unleash very vulgar and brutal ultra-right wing forces that will be turbo-charged by the disintegration of the EU.

“Brexit would accelerate the disinteration of the EU The only beneficiaries would be the ultra-nationalists, zenophobes, racists.

“I too would love to give a bloody nose to Brussels. I would love to see a result in a referendum which displeases Mr Junker, Mrs Merkel and Mr Cameron, but this should not be our criterion. Our criterion should be a broad, pan-European, democratic movement, for preventing another 1930s.”

This strikes me as a powerful and wise argument. What is now the EU was born out of the desire to prevent war, and the nationalism around in the language of “take back our nation” or “take back our borders” holds something which should have echoes of the 1930s.

People might argue that that was a different time and the same would not happen again. I fear they are wrong. As an example, my mind jumps to the radio play Look who’s back, broadcast September 2015. This is an English version of a novel by Timur Vermes, which imagines Adolph Hitler suddenly turning up today. Chillingly, the radio play translates the action to the UK. It gives a scarily credible picture of how someone of his ilk can rise to power which both gives an insight into what happened when Germany elected the Nazis, and a scary reminder that the UK is not immune to this.

The EU is not perfect, but does provide a protection against the extremist tendency. Even its lack of perfection is actually a positive thing, because it has enabled ongoing change to be core to the European project (and make Cameron’s much-trumpetted “renegotiations” look like a fiddling in the corner).

But Varofakis continues with some challenging thoughts about deepening EU democracy. This is tricky territory. Proponents of Brexit love to castigate the EU as “undemocratic” — though the charge is unfair — it manages to have a rich way to enable the elected European Parliament and the elected goverments of the nation states work together. From a British perspective, the charge that the EU is “undemocratic” is highly hypocritical — neither the House of Lords nor the bizarre mapping of votes onto numbers of MPs in the 2015 General Election sound democratic.

Towards the end of the interview Varofakis talks of ways to improve democracy in the EU. He has a point. Those who argue for Brexit on the grounds that the EU doesn’t change would do well to heed the sheer number of voices pushing for and enabling change in the EU. Surely our place is to be with them, working to make things better and not bleating from the sidelines, or blundering out after a referendum held in a fog of dis-information.