In the normal course of events, there is a Queen’s Speech at the start of each parliamentary session, and a prorogation at the end.

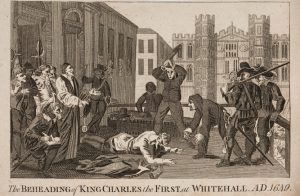

But there is a more extreme precedent: an unpliant parliament led to Charles I doing this. It produced a period of “personal rule” (1629–1640) — fuelling the resentments that led to civil war and his own execution.

Both Boris Johnson and Jeremy Hunt have spoken of a willingness to leave the EU without a deal. Perhaps they are wolf-whistling the more extreme members of their own party whose votes they need to become leader. But both face opposition from Parliament. The strong suspicion is that some MPs who have (so far) voted against attempts to prevent the UK leaving the EU without a deal would vote the other way if it were close to happening.

In this situation, the only way to stop Parliament voting down a “No Deal” Brexit is to stop it voting at all. Jeremy Hunt has ruled this out. Boris Johnson has not. There are rumours that he is actively considering it.

Legal challenges to prorogation

In principle, the decision to prorogue parliament is taken by the Queen on the advice of the Prime Minister. The Queen’s actions can’t be challenged in court, but former Prime Minister John Major has said that he’d seek a judicial review of Johnson’s actions if he tried this.

That was followed up by the news that Gina Miller has re-assembled the legal team that challenged the issuing of the original Article 50 notice, ready to act if Johnson tries this.

The result has been fury from Brexit supporters. Priti Patel accused her of trying to detail Brexit:

The Telegraph lambasted first Major and then Miller, claiming that “her claims to be standing up for democracy are fooling no one”.

On BrexitCentral’s twitter feed things were more strident. @brenda68676316 tweeted “When will this Woman stop thwarting our country? DEMOCRACY all the way! Please Please Please.” and @deanpaulmason added “Its about time she was investigated. People like her lie and get away with much. Maybe someone needs to hire a professional investigator. Things will come out on her. Bad things. Her ex husbands could say a lot as well.”

The courts would only say “no” if Boris Johnson were breaking the law. In all the anger and personalised language, people are overlooking the fact that this would be a court case, succeeding only of Miller (or Major’s) lawyers rather than the Prime Minister’s lawyers persuade the court.

People complaining are acting as if they think the courts are corrupt, or the Prime Minister is above the law. In that video clip, Priti Patel says that “the government was clear that Brexit means Brexit and we were going to leave the EU, instead we had a range of third party anti-Brexit organisations that chose to go to the court to derail the whole Brexit delivery.” It’s hard not to read that as saying that the delivery of Brexit matters and the law cannot stand in its way.

Tipping the balance

There have been prorogations in the past that were about more than an annual parliamentary cycle. In 1948, the Atlee government used this to circumvent Lords opposition to the Parliament Bill — the point was that the Lords couldn’t stop the bill, but could delay it for three parliamentary sessions. By proroguing, Atlee was able to make those sessions happen quickly. That might have been controversial, were it not for the fact that he had a majority of 145, and the opposition largely agreed on this proposal, so it was more-or-less certain that it would go through, so in this case the effect of prorogation was to accelerate the inevitable.

Now we are in very different territory. Proroguing parliament to stop it voting down something the Government supports is dangerously close to what Charles I did in (effectively) dispensing with parliament. It tilts the balance of power between government and parliament firmly in the direction of government. This is on top of the tipping of the balance in the government’s favour by the EU Withdrawl Act — which gives ministers a way to circumvent parliament in making the legal changes needed to deal with EU law being signed into UK law (and perhaps change things).

Hidden dysfunction of a referendum

In countries where referenda are frequent, they are a part of the normal democratic process. But in the UK the are so rare, that the sense is that they mean that parliament cannot decide, or parliament has failed. It’s possible to view the calling of the referendum on Scot’s independence as David Cameron seeking to over-rule the SNP MSPs who could otherwise claim their majority as a mandate for independence, and it’s possible to read the Brexit referendum as him also trying to over-rule his Eurosceptic colleagues. Those are explicit side-lining of the democratic process.

This sets up a dynamic of “the people” against “the government” (or “the governing elites”). Although I disagree with it, this makes sense of the Daily Mail headline “Enemies of the people: Fury over ‘out of touch’ judges who have ‘declared war on democracy’ by defying 17.4m Brexit voters and who could trigger constitutional crisis” after Gina Miller’s first case, forcing the government to seek a vote in parliament to trigger Article 50.

An anti-oedipal reading

Howard Schwartz has suggested a very useful way of thinking about the mentality behind political correctness. He suggests that a conventional reading of the Oedipus complex sees mother and baby as a pair, where the baby sees itself as at the centre of the mother’s universe. But that baby has to grow up in a world that doesn’t care if it survives. The symbolic father’s role is to introduce reality — helping the child to learn to cope with the external world (he uses the phrase “symbolic father” because this isn’t necessarily done just by the child’s biological father). He suggests that, in political correctness, the symbolic father is pushed out. Reality is denied, in favour of a world where everything is perfect — the baby is back at the (imagined) breast. The idea that things can go wrong is unacceptable. It’s a useful idea, which makes sense of the way in which things around inclusion, which should be really positive, can backfire. Instead of celebrating diversity, it creates a world where it can’t be seen.

Schwartz’ work is much more applicable than political correctness. One of the themes I’ve found useful is what he calls the “primæval mother”. This has nothing to do with a child’s actual mother, or mothers in general, but is what would happen if a creature were constructed out of all of an infant’s paranoid schizoid fantasies — it’s the creature causing the infant’s cries and fears. This is an irrational (but intense) sense of “something bad” being there in addition to the world where difference can’t be seen.

On these terms, an attempt to prorogue parliament is an attempt to push out reality (the paternal function) — that parliament does not support a no deal Brexit. If reality were around, it would include a credible plan for a no deal Brexit. But this isn’t relevant. Reality has instead to be denied. The strong emotions in favour of doing this are not driven by logic, but that web of intense and terrifying projections that come together in that “primæval” figure make sense of how people are talking.

The courts, in this case, are holders of that paternal function of representing reality. In the anti-oedipal mindset, this is detested and has to be rejected — hence the stridency of the language of those affronted by Gina Miller threatening legal action.

And as a footnote — the anti-oedipal language sometimes attracts criticism because of the gendered language. This is about what we learn as children, not about the adult world. In this case, it looks very likely that the paternal function is being held by a woman (Gina Miller) and would end up in the Supreme Court (which now has a majority of women judges).

A way out

However it is theorised, the possibility of the Prime Minister seeking to ask the Queen to prorogue parliament in order to stop it voting down something he believes in represents a major constitutional change. A prorogued parliament would also be unable to remove the government in a vote of no confidence.

The most likely outcome seems to be that parliament would vote that it has no confidence in the government before it could be prorogued. At that point, parliament itself is re-asserting reality. But we are in dangerous territory when things have to go this close to the wire. Part of the danger is what constitutional precedent could enable. A much bigger danger is what all this does to the national psyche.