The widespread anger at lockdown-breaking parties at Downing St in May 2020 is justified. But it is also a surprise that anyone is surprised. Johnson’s unsuitability for high office has been obvious (at least) since his time as Foreign Secretary. John Major has described Brexit as “the worst foreign policy mistake of my lifetime”: partygate, serious though it is, pales in comparison beside that.

The widespread anger at lockdown-breaking parties at Downing St in May 2020 is justified. But it is also a surprise that anyone is surprised. Johnson’s unsuitability for high office has been obvious (at least) since his time as Foreign Secretary. John Major has described Brexit as “the worst foreign policy mistake of my lifetime”: partygate, serious though it is, pales in comparison beside that.

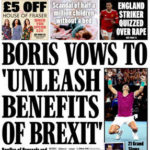

As “Partygate” comes to its (first) climax there’s the announcment of a “Brexit freedom bill” (to unwind EU-derived law), and the front page of the Daily Express says “Boris vows to ‘unleash the benefits of Brexit’”.

I can’t be the only person who years echoes in that of “unleash the dogs of war” — a corruption of “Cry ‘Havoc!’, and let slip the dogs of war” in Shakespear’s Julius Caesar. Not a good omen.

Partygate anger

Anger is a pretty raw emotion. I suspect that what is being expressed around “partygate” includes pent-up frustrations over Covid, worry over the economic situation, anxiety over empty supermarket shelves, and fears over the direction of Brexit.

The events of “partygate” happened around the time of Dominic Cummings’ trip to Durham — in defiance of Covid rules. At the time, I wrote something where I floated the idea that, for all the anger this elicited, he had connected with those who were frustrated by the Covid rules.

I fear that we are seeing something similar now — anger at Johnson from his opponents is masking the secret approval of people who broke the rules, or would like to have done, or who seek to wish Covid away.

In 2019 I wrote something about the (then) most recent Audit of Political Engagement, which suggested that a majority in the UK would favour a “strong leader who would break the rules”. Might those people now be admiring the Johnson government for its willingness to break the rules? That article feels horribly prescient — especially as it names the possibility that Johnson might be opening the door to something worse.

Libertarian rather than “right wing”

Opposition to Covid rules is coming from a variety of directions — notably conspiracy-theorists dismissing Covid as a “plandemic”, anti-vaxxers who favour “natural immunity” and libertarians who object to the rules/guidelines on principle. The libertarian part of that doesn’t map perfectly onto “right wing” or “left wing” — the “Covid Recovery Group” of Tory MPs has been leading the charge from one side, but so has Piers Corbyn (brother of the former Labour leader).

This emphasis on personal liberty feels quite different from the position in the preamble to the Liberal Democrat party’s constitution, which says Liberal Democrats “exist to build and safeguard a fair, free and open society, in which we seek to balance the fundamental values of liberty, equality and community, and in which no-one shall be enslaved by poverty, ignorance or conformity.” Linking liberty and community is a million miles from denying the grizzly reality of Covid, reflected in intensive care wards up and down the country, in order to demand “liberty” at others’ expense.

In a post late in 2020 I floated the idea that the government was behaving as if “obeying the rules” rather than “following medical advice” would save people from Covid. There were questions about how well the government was following the advice of SAGE (the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies). In contrast, friends in Belgium and Germany spoke of public health officials being centre stage and politicians reflecting that advise in rules. I now need to nuance that. Perhaps a better reading was of a Prime Minister deftly saying “obey the rules” and conveying “do what I say”, with the implication that he is also exempt.

If that sounds twisted, a key might be in a Lacanian understanding of perversion — “the rules exist but they don’t apply to me”.

The creep to a “presidential” system

In Newsnight on 25 January Jacob Rees Mogg spoke about the possibility of a change of Tory leader and floated the idea of that leading to a General Election: “we’ve moved, for better or worse, to an essentially presidential system and therefore the mandate is personal rather than entirely party”.

Rees Mogg must know that this isn’t true, but I fear this might be a pretext for a General Election later this year (before the tide of opinion has turned on Brexit). Opposition parties would cry foul, but as long as Tory voters can be persuaded that this is fair, there is a risk of the Tories coming back, albeit on a reduced majority.

The lack of criticism of Rees Mogg’s remark is telling. It was mostly spun as a challenge to Tory MPs to back Johnson (affirming the pretence of “presidential” authority), rather than as a blatant attack on our democratic system. Worryingly it fits in with a trend to accrete power in Downing St, without stronger checks and balances on the exercise of that power.

Brexit “freedoms” bill

On the same day as Sue Gray’s report was released (minus the bits the Police are investigating), the government announced a “Brexit freedoms bill”. The press release says:

A new ‘Brexit Freedoms’ Bill will be brought forward by the government, under plans unveiled by the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, to mark the two-year anniversary of Getting Brexit Done.

The Bill will make it easier to amend or remove outdated ‘retained EU law’ — legacy EU law kept on the statute book after Brexit as a bridging measure — and will accompany a major cross-government drive to reform, repeal and replace outdated EU law.

What should send shudders down the spine, particularly in the light of Rees Mogg’s comments, is that there is a limit to the amount that parliament can meaningfully scrutinise, so the promise to “make it easier to amend or remove” EU-derived law inevitably means decisions being taken by ministers — moving more power from parliament to the government.

The Guardian rightly raises the spectre of this cutting employment and environmental protections, and quotes Emily Thornberry pointing out that the government has not taken advantage of is freedom to depart from EU practices on VAT to help people struggling with fuel bills. The Guardian also flags up the spectre of softening data protection legislation. That may sound obscure, but people who have read Chris Wylie’s Mindf*ck: inside Cambridge Analytica’s plot to break the world, will be aware that the misuse of data is already a threat to democratic processes, and might well have been what tipped the EU referendum in favour of Leave. The implication is that our politics needs better, rather than weaker, data protection rules.

Too early for the F— word

At the back of my mind in this saga — as in Donald Trump’s attempt to hang on to power even after losing the US Presidential Election — is the spectre of fascism. Treating what happened in the 1930s as unspeakably awful carries the complacent implication that it could never happen again. The brutal reality is that the chain of events that ushered in fascist regimes in Europe in the 1930s were accidents after accidents as people struggled to deal with difficult and frightening times. We are struggling to deal with difficult and frightening times now.

Some of the psychoanalytic work around the rise of fascism suggests that it worked by people feeling a close identification with the leader, so it became “my Führer”. The brutality was directed at the “enemies” of that leader. It cuts out a sense of “community” or “common good” in favour of loyalty to the leader — who is above the rules.

We have a government that’s happy to make Covid rules that sit loose to medical advice and (we now discover) to break those rules, to abandon the freedoms and protections we had as EU citizens in the name of “Brexit”, to seek to overturn court judgements that go against the government (with the implication that the government is above the law), to move power from parliament to the government without any consultation and is now attaching the word “presidential” to the Prime Minister.

That doesn’t look good. If this is the “benefit” of Brexit, then the sooner we are shot of it the better. We’re not (yet) in fascist territory, but it is worth remembering that the EU came out of the horror of the Second World War. It began in the desire to ensure that this never happened again. If collective processes are pulling us in that direction, then we’d have to begin by leaving the EU and coming up with some stories to justify that. Partygate and the “’Brexit Freedom’ bill” give a taste of what has been unleashed.