I didn’t think much of Donald Trump when he first emerged as a potential candidate for US President, and he has lived down to my expectations. I smiled when a friend sent me a photo of a pumpkin carved for Halloween with a caption that it was “hollow, orange, and thrown out in November”.

But a clear that there was more than that in play came when an American friend told me she had sent in her mail-in ballot (for Biden) and I found myself close to tears. My reaction to the actual election process has been far from neutral. It is as if this is much more than the election of a foreign leader.

At the back of my mind is a memory of one of the more grizzly days in the sorry saga of Brexit. In gallows humour, I commented to a friend that “Theresa May has just rung The Samaritans. Angela Merkel took the call. Ambulances are on stand by”. Behind the humour was a sense of horror — at some level identifying with the leadership of the country of which I am a citizen, yet also profoundly disquieted by the direction they were leading in.

Underneath the rational discussion of policy and politics, there is a not-so-rational sense of national identification.

For a British citizen to identify — albeit awkwardly — with the British government is one thing. To find myself identifying with the US one — albeit with visceral horror — is quite another. It’s a testament to how far globalisation — global interconnectedness — has gone.

One way to see this is that it is about containment. If national identity shapes people’s understanding of themselves, and people’s understanding of themselves shapes national identity then things are stable. Stories from the past shore up that identity, whether those are myths like King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, or stories of The Blitz that are only now sliding out of living memory. But that circle breaks down when national identity erodes a little.

Globalisation is here to stay

David Goodhart’s The Road to Somewhere suggests that the big distinction in contemporary politics is between people who see themselves as “citizens of anywhere” and “citizens of somewhere”. He has a point, in that many people now think much more globally than their grandparents. But, in my experience, people who are deeply rooted in one place are now very rare in the West. Goodhart’s “citizens of somewhere” are defined against the “citizens of anywhere”.

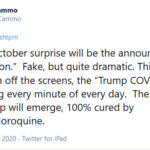

This matters because globalisation is here to stay. As the results of the US Presidential election started to come in, I saw a tweet from a Brexit supporter in the UK, in a period when Trump seemed to be ahead, keenly predicting that he would be elected and that this would be “the end of globalisation”. That makes sense as a reaction against globalisation, but not as more than that.

I am saying that globalisation is here to stay because we have become interconnected. In the UK, we can watch US election results arriving in real time. I recently took part in a conference in Australia on line from my flat. Trade barriers can impede global trade, but all this does is to build up dis-equilibrium. Among the ways round that is the transfer of ideas. The only way to stop globalisation is to get rid of the technological advances that have made it possible.

Anti-globalisation is a reaction against globalisation. Like most reactions against something, it is defined by what it reacts against. The role of anti-globalisation protest is to express the emotions of people reacting against globalisation. It isn’t a rational engagement with globalisation. A sharp example is the “Make America Great Again” hats Trump supporters were wearing in 2016 — which had “made in China” labels inside. If this were actually about stopping globalisation people wouldn’t have worn “made in China” hats. But if the purpose was to express the anger elicited by globalisation, then where the hats were made didn’t matter.

Escapist support for Trump

This sheds some light on some of the support for Trump, both in 2016 and in 2020. What Trump succeeded in doing was to mobilise people’s anxieties and present himself as the answer. This was never about “making America great again”. It was about expressing the anxieties of people afraid because America is losing its place as the world’s pre-eminent nation.

Even the disgust at Trump’s antics across the world may well have helped mobilise his supporters — with the not-so-coded message that, if the rest of the world stands against Trump then, then he is giving voice to those in the US who feel threatened by rest of the world and want a hero.

One of the symptoms of maladaptation is a sharp binary thinking — splitting into “good” and “bad”. It’s an indicator that things are already not working. Biden’s narrow victory might be good, in that it forces attempts at reconciliation rather than the “triumphalism of the 51%” but this can’t be done by turning the clock back. Biden’s age means he can present as a “stable grandfather”, which helps defuse the situation. The task will be for him to hold that place of stability while the US engages with its changing place in the world.

The Brexit parallel — and a way forward

Readers of this blog will be aware that I have a very dim view of Brexit. One of the parallels between Brexit and Trump is that both contain a big slice of flight from reality. Boris Johnson’s government is having a hard time negotiating a viable Brexit because the vote to Leave the EU had a great deal more to do with an expression of pain and frustration at Britain’s changed place in the world than it had to do with the realities of leaving the EU. US presidential elections take place every four years, so there was an obvious way for their 2016 decision to be reversed. There isn’t an automatic route to revisit the UK’s 2016 decision to leave the EU, which makes reversing that more difficult (and implies more economic hardship before that happens). But what the US and UK have in common is a reaction against a globalisation that doesn’t actually stop it. All that the votes for Brexit and Trump did was to give voice to those trying to deny the reality of globalisation — which makes globalisation harder to engage with.

What both the US and UK need is leadership that helps both countries engage with a world that is changing rapidly. We could do worse than look to Germany and the work the Germans have done since the disastrous denial of reality that happened there in the 1930s, and to the way the EU has enabled diverse nations to work together to find a new place in the world.

Thank you!!1