Concern over migration is shaping up to be a EU-wide issue — it is frustrating that it is an issue in the referendum debate as if this is not something we share with our EU partners.

Last weekend’s elections in Germany have sent shockwaves because of the progress of the right-wing, anti-immigrant Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). Writing in The Guardian, Philip Oltermann also points out the success of some pro-refugee candidates as an illustration of the increasingly complex and fractured nature of the argument.

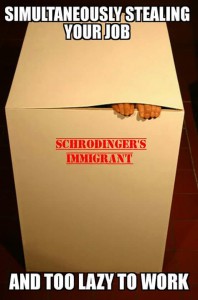

It sounds very familiar: in the UK the proponents of Brexit are pushing an anti-immigration case to “take back control of our borders” while Liberal Democrats are tending to point out the value of immigrants. In narrowly-financial terms, the awkward reality is that immigrants to the UK contribute substantially more in taxes than they take out of the system in benefits. Even the argument to restrict benefits to new arrivals is questionable: if someone comes to the UK, claims benefits while they settle, starts earning and starts paying tax and more-than pays back what they received, then the “benefit” payments look like a prudent investment. The idea’s been pithily summed up in the idea of Schrödinger’s immigrant: simultaneously stealing our jobs and too lazy to work.

It sounds very familiar: in the UK the proponents of Brexit are pushing an anti-immigration case to “take back control of our borders” while Liberal Democrats are tending to point out the value of immigrants. In narrowly-financial terms, the awkward reality is that immigrants to the UK contribute substantially more in taxes than they take out of the system in benefits. Even the argument to restrict benefits to new arrivals is questionable: if someone comes to the UK, claims benefits while they settle, starts earning and starts paying tax and more-than pays back what they received, then the “benefit” payments look like a prudent investment. The idea’s been pithily summed up in the idea of Schrödinger’s immigrant: simultaneously stealing our jobs and too lazy to work.

Anxieties over immigration are widespread in the EU. Proponents of Brexit who behave as if only Britain has this problem and needs to “defend itself” are well out of touch with European reality.

This is the crucial point. Many of our big problems are shared with our European neighbours. The days when nation states could solve major issues in isolation are gone. That is a part of globalisation — it goes with the ease of international travel, the rise of global trade and the internet. It is essential to be working closely with other nations, and doing that as part of a democratically-regulate European single market is essential.

Part of the single market is a single labour market, so that people can travel to work as well as sell the fruits of their work across the EU. Scare stories about EU migrants taking British jobs need to be heard in the same breath as NHS hospitals solving staff shortages by recruiting outside the UK.

With a nasty civil war in Syria we do face the problem of lots of people needing to leave their country. Jordan and Turkey are bearing the brunt of that humanitarian crisis. “Fortress Europe” could pull up the drawbridge. That is hardly civilised behaviour. It is also not in our long-term interest: the crisis won’t go on for ever, and treating people well when they need our help will pay dividends in the future.

One of the Europe-wide problems we face is the rise of the far right. Seeking to leave the EU is a British response to a pan-European problem in the rise of the far right.

One of the chilling experiences of the 2015 general election was canvassing in an almost-exclusively white, medium-income area and having people express discomfort at austerity in terms of fears of immigrants, which meant they were wanting to vote Conservative to cut down on migration — and therefore vote for the Conservatives who were (and are) pushing for needlessly-deep cuts. A scary example of an irrational “fear of migrants” leading people to vote for the austerity that was hurting them.

The film Look who’s back has the ruse of imaging Hitler turning up today. When it was revised as a radio play for broadcast in the UK it was chilling because it was credible — both for explaining what happened around Hitler’s rise in Germany, and how that could happen in the UK today, with a less-than-sane Hitler mobilising people’s primitive fears to act against their own best interests. It is all too convenient to act as if Nazism was a uniqely German problem: Mosley’s black-shirts, anti-semitism in the 1930s and the fact that we British pioneered concentration camps in the Boer war are reminders that we too have a capacity to head in that direction. Mark Mazower’s book Dark Continent traces this as a Europe-wide danger. One of the reasons for forming the EU in the first place was to protect us all against lurches in that direction.

It’s really important that a panic reaction to the reality of people needing to leave Syria, and an emotional reaction to fears of migrants, don’t lead Britain to fall out of the EU and discover the hard way that the fears of migration are mis-placed.