For some time now I have been working my way through the Hindu epic the Mahabharata, serialised on Indian television in the 1980s, and now on youtube. At its core is a huge war between two sets of cousins. It’s sometimes cast as a war between truth and untruth. Like all wars, its causes are complex.

Part of the explanation is that king Vichitravirya’s elder son, Dhritarashtra, was born blind, so his younger brother, Pandu, was named Crown Prince. Dhritarashtra succeeds to the throne after his brother’s premature death. That contains the seeds of a deadly for succession between the sons of Pandu and of Dhritarashtra — not helped by Dhritarashtra’s blind loyalty to his son Duryodhan, despite his obvious rashness, which stands in marked contrast to the wisdom of Pandu’s elder son Yudhishthira.

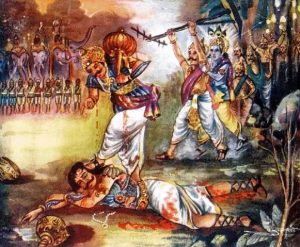

This evening I’ve been watching episode 92. In which Duryodhan, the last of Dhritarashtra’s sons died. There is a telling exchange between Dhritarashtra and his courtier, Sanjay:

Sanjay: The truth of this painful moment is that war is not a solution to any problem. It can only pierce the heart… You could have stopped this war at any time.

Dhritarashtra: Yes, I could have! Whenever I tried to stop this war, my ambition and my filial love stopped me. But now there is no ambition… and no son! I stand alone amidst the ruins of my dreams. The war which ended with the death of my son is still raging within… my heart. I am both the sword and the shield. I both attack and defend myself… Even if I win, I will still lose.

Oh Duryodhan! I have done you an injustice. People nurture their sons on honey. I nurtured you on the poison of my ambition. The result is that your corpse lies untended on the battlefield

… and Brexit

In terms of Brexit, I’ve been very struck by the war-like language. I’ve heard people say things like “we won two wars, why should we give in now?” We’ve heard Boris Johnson liken our European neighbours to guards in prison camps administering punishment beatings.

More recently, we’ve heard Boris Johnson speak with enormous positivity and ambition, as if, demanding a little more, with enough “positivity” is bound to work.

This evening came the news that “Boris Johnson tells Jean-Claude Juncker there is ‘no prospect’ of a Brexit deal unless the backstop is abolished”. As the purpose of the backstop is to ensure that, if more sophisticated options fail, we don’t lurch back into sectarian violence in Ireland.

The Mahabharata

The parallel might not seem exact. But the underlying human story is. I’m mentally bracketing Boris Johnson with Duryodhan, as a figure blinded by ambition, and too willing to use the language of fighting and of actual war, as if the price of war and the risk of losing can be ignored.

That speech from Dhritarashtra is a reminder that there’s a story behind Duryodhan’s ambition, cocky over-confidence, and lack of wisdom. There’s a story behind Dhritarashtra’s blindness. There’s bad behaviour. There are explanations. The explanations don’t justify the bad behaviour. In this case, part of the price is that Dhritarashtra’s failure to stop the war has led to the death of all of his sons (and countless other soldiers).

What I am hearing in this is a timelessness. There’s something of the fallibility of the human condition, and the challenge to rise above this.

In the Mahabharata, part of that “rising above” takes place as the war is about to start. Arjuna, one of Yudhishthira’s brothers, tells Krishna, acting as his charioteer, that he doesn’t want to fight. The Hindu text the Bhagavad Gita is the dialogue in which Krishna talks of duty, and of the timeless, before Arjuna is able to take up his bow.

In the context of the European Union, part of what feels like a very similar mindset is in the vision of the Schuman Declaration which led to the formation of the European Coal and Steel Community. The reasoning was that coal and steel were the essential raw materials for mid twentieth-century warfare. Treaties can be broken, but integrating those industries made war impossible. That was a brilliant mix of idealism and pragmatism.

The Brexit crisis is very real and very threatening. It’s easy to see it as unprecedented. What my brush with the Mahabharata is doing is to put me in touch with the timelessness of the frailty that lies behind both that war and Brexit. It says something about duty and about context. In the Mahabharata, the sons of Dhritarashtra behave as if sure that right is on their side. The sons of Pandu seem less certain, but give it their best shot. Their strength lies in not being certain, which means there is room also to seek wisdom.

That seems to be the approach needed to find a way out of the crisis of Brexit. Vaulting ambition and excessive confidence might come naturally both to Boris Johnson and to Duryodhan, but this leads to a high price and not a wise outcome. I am very much hoping that what is going on among our parliamentarians at the moment is finding a way to let wisdom rather than certainty into the process.