This was an election where Labour promised huge increases in borrowing, championing “the end of austerity” a “green industrial revolution” and a large number of nationalisations. Those with long memories will think of the situation the country was in during the 1970s. It’s a message that caught the idealism of young people. The snag is that it’s an idealism that risked also doing real damage.

On the Conservative side there was the option of Boris Johnson, full of confidence and bravado, promising an unattractive Brexit, avoiding media scrutiny and producing campaign claims which rarely survived the attentions of fact-checkers.

A journalist at the Huntingdon count described this as a “brutal” election. I was relieved to have my perception confirmed from someone outside the party-political bubble. The brutality was striking because there was so little meaningful discussion of policy. It felt as if the brutality had taken up the void left by the failure of meaningful discussion (or perhaps the failure of discussion created the void for brutality to grow).

My own view is that, with a Labour leader of the calibre of Hilary Benn or Keir Starmer, things would have been very different. Labour would have been ahead in the polls. The Conservatives would have been avoiding an election and lost heavily if backed into one. That would have enabled a much more mature thinking around Brexit, and quite possibly led to Brexit falling away. I am thinking that particularly because Brexit can be read as a “reaction against” from people who feel abandoned. A trustworthy leader would have removed the “reaction against”. A trustworthy leader of the opposition could have enabled some constructive cross-party working.

New Labour under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown had a vision of enabling the less wealthy. Significant effort was put into addressing social exclusion. I was excited in this General Election by the Liberal Democrat promise of free nursery places because I’d heard the New Labour arguments that a child that spends its first five years in poverty is much more likely to spend the rest of its life in poverty. There’s a generosity and a gentle idealism in that position.

Melanie Klein: envy, and what goes with it

Under Corbyn this tipped over into envy. Melanie Klein made a really helpful observation that envy isn’t so much “I want what you’ve got” as “I want you to not have what I’ve not got”. There’s a brutality in that.

Up to a point, the brutality is understandable. People have lost out as a result of the 2008 financial crash. Labour supporters attacking “austerity” forget that they, Liberal Democrats and Conservatives all had cuts in their 2010 manifestos, because the fallout of the crash meant there was an urgent need to reduce government spending. But envy isn’t particularly rational. It easily becomes an attack on those supposed to have (or supposed to be part of having taken).

Klein links this to what she calls the paranoid schizoid position — by which she means what is around for babies in intense reactions to things that seem either good or bad, and is characterised by lots of aggression, in the early months of life. She suggests that what then develops is a “depressive position” where an infant can begin to get in touch with something more nuanced which is neither fully-good nor fully-bad. She suggests that we have access to these two ways of being throughout our lives — and can regress to the paranoid schizoid in various stressed situations.

Tactical voting

In this election we saw lots of calls for tactical voting. On first sight, this seemed to be an attempt to get round the failings of the “First past the post” system, to avoid having a pro-Brexit Tory government. But on reflection, I now think there were two different priorities which sometimes overlapped. One was to get a government that would support a second referendum on EU membership. The other one — predominantly espoused by Labour — was to get rid of the Tories and get a Labour government. These two overlapped in as much as Labour supported remaining in the EU, but it’s far from clear that that as high a priority as the Liberal Democrats. More of a paranoid schizoid mindset on the part of some Labour supporters would have defaulted to “Labour = good” and “Tories = bad”, which explains this other way of thinking about tactical voting.

This mindset was there in Corbyn’s insistance that he wouldn’t countenance anyone but himself leading a temporary government of national unity in the last parliament, despite the fact that the Tory MPs who had lost the whip wouldn’t have backed him. That led to extraordinary attacks on the Liberal Democrats for saying that Corbyn didn’t have the numbers in parliament. Unfortunately, he really didn’t have the numbers.

I fear this also coloured Labour in deciding to go for a General Election. When Johnson sought one, the other parties could have refused and insisted instead on a cross-party government to sort out the Brexit shambles. But that binary, paranoid schizoid thinking would explain Corbyn’s insistance on seeking to win an election.

There was a serious attempt to broker a “Remain alliance” in order to avoid pro-Remain candidates standing against each other, with a view to getting a pro-Remain parliament elected to deliver another referendum. Liberal Democrats, Greens and Plaud Cymru participated, but Labour refused. The obvious reading was that this was an attempt to avoid co-operation, prioritising a Labour government over a pro-Remain arrangement, or could only think in terms of Labour being the only “good” option.

In the 2019 General Election I was the Liberal Democrat candidate for Huntingdon constituency. At a very early stage in the campaign, I received an email from someone who I assume was a Labour supporter / member (though not writing in an official capacity) saying “could you give is your 5090 votes” (which is the number we had in 2017). The person clearly didn’t realise that a candidate doesn’t own the votes of those who vote for them, but this is also a very simply piece of binary thought — where the thinking can only handle a choice between two options.

Huntingdon is a Conserative constituency. In the campaign I met lots of people who were used to voting Conservative but now couldn’t because of how extreme they had become, but who also couldn’t vote for Labour because of Corbyn. Those people were coming to the Liberal Democrats, and it seems likely that they would return to the Conservatives if Liberal Democrats didn’t stand. That’s a more nuanced position than simple “tactical voting”.

Yet at various points in the campaign I had appeals by email from Labour supporters to stand down and twitter exchanges at varying levels of aggression which seemed to boil down to “get out of the way”. Formally, the Liberal Democrats have a policy that this is not a local party decision — partly because the assumption is that there will be a reciprocal arrangement elsewhere. I suspect that it’s also there to protect candidates from this sort of attack. But I don’t remember anything of the severity of 2019 in previous elections.

I could sell all this as Labour aggressively pushing an envy-laiden manifesto and alienating voters.

Envy at work

A few stories caught the papers of Liberal Democrat candidates saying their supporters should vote Labour in constituencies where Liberal Democrats were likely to finish third, but a conspicuous absence of Labour candidates doing the same in reverse.

In South Cambs polling was putting Liberal Democrats and Conservatives neck-and-neck with Labour well behind, yet the Labour candidate gave an interview just before the election claiming that polls were being used to manipulate the electorate and that he was in fact the true “remain” candidate. That sounds like “Labour at any cost”.

Much more seriously, I’ve since heard stories of seats where Liberal Democrats were poised to defeat the Tories and Labour sent lot of activists in to switch people from Liberal Democrat to Labour — preventing a Liberal Democrat victory but not delivering one for Labour. On twitter @TheRedRoar posted a screenshot of an email from London Labour asking people to go to Finchley and Golders Green (where a 25 point swing to Liberal Democrats had nearly enabled Luciana Berger to win).

In the Cities of London and Westminster a swing of 19 points nearly enabled Chukka Umana to win, and one of activists, Amanda Jeyaretnam, tweeted:

“There’s evidence. I was a canvassing lead in Cities and Westminster. Lab activists flooded the borough. At first small groups, prob local activists but in the last 2 weeks they arrived in large groups of about 50. We told residents a vote for Lab would give a Tory win. It did.”

In Wimbledon, Liberal Democrats had a swing of +22.7 points and lost by just 628 votes (with Labour 7202 behind them), but in the face of a campaign delivering such a swing, journalist Paul Mason (@paulmasonnews) tweeted:

“I’m in Wimbledon with Labour candidate @jackieschneider – stuff the Libdems and their fantasy bar charts… it’s a two horse race in this area #VoteJackie”

and in that constituency, LibDem activist @KateTheSaboteur added:

“Yes, in wimbledon they bussed in canvassers from elsewhere, then tried to claim that as the ‘bigger ground game in the area’. I never once actually saw labour canvassers out in wimbledon. I understand they were bussed in for photo ops.”

It’s hard not to read these as envy leading people to destroy what they couldn’t have. Those Labour activists would have been better off going to seats where Labour was close to winning.

The tactical voting problem: were Labour in favour of Remain?

Earlier in this post I referred to the different priority over tactical voting between those wanting to stop Brexit and those wanting to get a Labour government. Those could be read as overlapping — Labour were promising another referendum. There is a double hitch here:

- Labour were proposing an impossibly-tight schedule: three months to negotiate a “new” deal and three months for a referendum. The Electoral Commission have been suggesting that a referendum should be given at least a year. For this to get a result people accept it should be preceded by a careful listening process, so there would have been a serious risk that Labour’s timetable bent the referendum process so far that it secured a second Leave vote.

- In several hustings my Labour opponent said he thought the outcome of a further referendum would be the same as last time. It’s hard to see how Labour could achieve a deal significantly better than Theresa May or Boris Johnson (because all forms of Brexit involve economic harm to the UK). If a Labour government had the chance to borrow as extravagantly as they were promising, we would be in a much poorer economic position to face the shock of Brexit, making Brexit under a Labour government even more of a risk than under the Tories.

The fallout

Envy is deeply destructive, whether it is envy of “the rich” in economic policy or envy of other parties in seeking power.

New Labour managed to get a long way from the politics of envy. In Kleinian terms, they managed the sort of nuance that is characteristic of the depressive position. In rejecting that, Corbyn took Labour into the extremes of the paranoid schizoid, where everything is stark and pragmatism is impossible. In that place the nuances needed for co-operation can’t be thought of.

Liberal Democrats had said that we couldn’t form a coalition either with Labour under Corbyn or Tories under Johnson, but could support a minority government in as much as that minority government was doing things consistent with the Liberal Democrat manifesto. The place Labour was in meant the subtleties of that couldn’t be heard — unwillingness to form a coalition put us on “the other side” as “yellow Tories”.

On social media I had a string of encounters with Labour supporters arguing that there was fundamental bias on the part of the Liberal Democrats towards the Tories as we’d not chosen to go into coalition with Labour in 2010 — forgetting that a coalition with Labour in 2010 would still have been 8 seats short of a majority.

The Liberal Democrat performance

I do think that the Liberal Democrats nationally made some significant mistakes in the 2019 campaign. But I also remember an observsation from Norman Lamb when he was standing for party leader, that the Liberal Democrats to best when Labour is credible. His point was that if “middle England” look at the Labour leader and think “fine”, then they can take the risk of voting Liberal Democrat. If the Tories can put the Labour leader’s face on a poster and scare people into voting Tory, Liberal Democrats struggle. For many people in 2019, Jeremy Corbyn was somewhere between “scary” and “irresponsible”. Perhaps some of the Liberal Democrat mistakes wouldn’t have happened if Labour were credible, and in that situation would also have mattered less.

Conclusion

The 2019 election has yielded a perverse result. The result makes most sense as a “we don’t want Labour” vote, so it is a mandate against Labour rather than for the Tories.

It is telling that there are stories of Tory candidates missing hustings, Boris Johnson not taking part in debates and interviews in the election and rumours of his staff keeping him out of the media. That’s not the strategy of a party that is winning. It is the strategy of a party that’s trying not to do anything to stop the other side losing.

Support for Brexit seems to have been waning — not least because the older votes who wanted it are dying and the voters coming onto the register are more pro-EU. We’re now in a situation where a mandate against Labour is functioning as a mandate for a Tory Brexit policy which they refuse to put back to the voters. If they were confident that it was still the will of the people, they’d have no problem having that a referendum to confirm that.

This is dangerous, both because of the Brexit it threatens, and because of the divisive, “either-or” paranoid-schizoid thinking that it has put centre-stage.

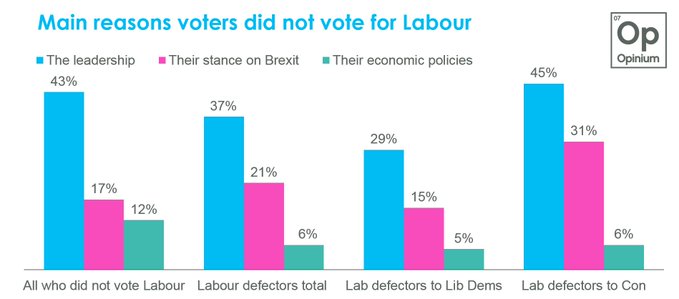

Postscript 1: information from Opinium

After writing the above, I came across a tweet from Opinium which shows the Labour leadership as the biggest reason for people to defect to other parties, by a significant margin:

Postscript 2: Ashcroft Poll

On 11 February 2020 The Independent ran an article saying that “Dislike of Corbyn to blame for Labour’s election disaster, not Brexit”, drawing on a poll conducted by Lord Ashcroft’s polling organisation.